Geschäftsstelle der Polonia in Berlin – Biuro Polonii w Berlinie zaprasza na wyjątkowe spotkanie na żywo z aktywistkami z dwóch niezwykle inspirujących organizacji: Dziewuchy Berlin […]

Tag: polish women

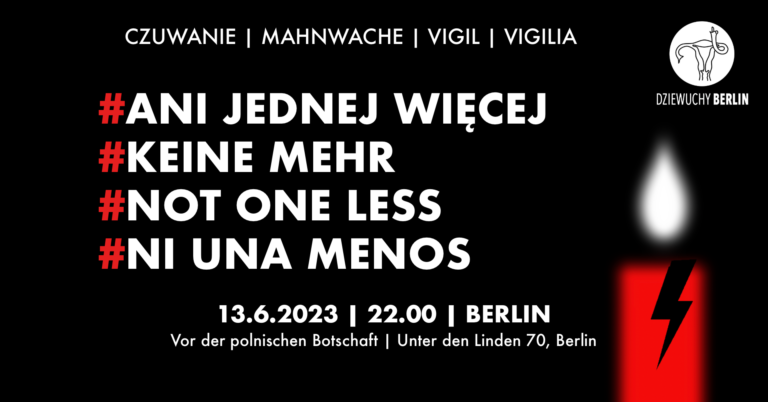

13.6.2023 Ani jednej więcej. Czuwanie. Keine mehr. Mahnwache.

(wersja polska poniżej, English below) 13.6.2023 | 22.00 | Vor dem Gebäude (Baustelle) der polnischen Botschaft / Przed gmachem (placem budowy) Ambasady Polskiej | […]

Szczecińska Manifa

W sobotę 11.03 byłyśmy w Szczecinie na Manifie, która po kilku latach wróciła do tego miasta. Hasłem przewodnim było: “Macierzyństwo to wybór”, które zawiera w […]

Women’s March Berlin – Personal View

Women’s March Berlin Text: Helena Kargol Last year we marched. Today we march again. Next year we will march again. I am so proud to […]

Solidarity with Polish women! NOW!

Solidarity with Polish women! NOW! CALL for ACTION! More than a year ago thousands of Polish women successfully took to the streets wearing black to […]